On the Fourth

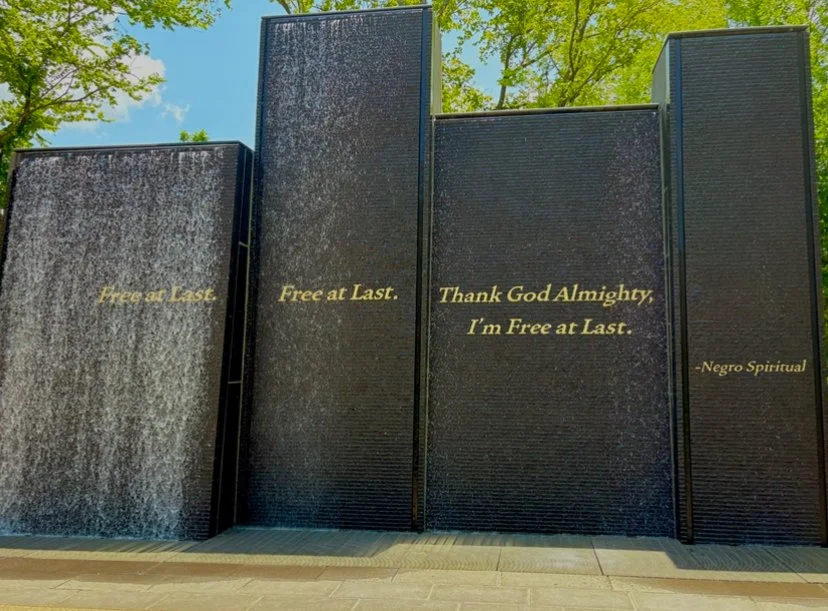

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama

This weekend marks the 249th anniversary of American independence from the British crown, and I cannot muster any words of pride for the only home I have ever known.

I did not feel this way a month ago for Juneteenth, the day marking when enslaved peoples in Galveston, Texas, learned of their freedom two and a half years later than they should have. Moved by the spirits of the late, great leaders, activists, artists, writers, and freedom fighters who came before me, I thought deeply of my own enslaved ancestors—Luvenia Jones, Caroline Leath, and Lewis Leath—and what my family has accomplished in the one hundred fifty-seven years since Black Americans have been recognized as free citizens of the United States. I felt gratitude and joy, in addition to grief, because Juneteenth, to me, celebrates people, a people I love.

Independence Day, on the other hand, commemorates country—a people and their most fundamental principles at its founding and across time. On the Fourth, my fellow Americans champion our independence, freedom, liberty, pursuit of happiness, and incomparable strength between bites of chargrilled hamburgers and hot dogs. They honor the brave sacrifices of our forefathers stitched into the reds, whites, and blues of our tank tops and beach shorts. They celebrate themselves, “we the people,” for being the prophesied benefactors of this great democratic experiment as we watch fireworks burst in air. Yet, instead of reigniting the love and reverence I felt so easily only a few weeks ago, all I have are questions: What has my country achieved with its independence after nearly two-hundred and fifty years? And is it deserving of patriotic fireworks?

For a long time, I could not pinpoint the tension between the two dates, why one liberation resonated with me more than the other. Race, which is to say the problem of racial, anti-Black slavery, is the only significant difference between the two freedoms. The works of Frederick Douglass and W.E.B. DuBois presented that binary most clearly. In 1852 Douglass asked, “What do I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence?” implying his Independence Day had yet to come. DuBois split the country by a racialized ‘two-ness’ with his “double consciousness” and “veil” conceptualizations. It would be easy for me to rely on their segregation of Black and white America, claim that my preference for Juneteenth is due to identity and cultural tradition, and assert that the freedom of the Black American people is the one that matters most to my lived experience as a Black American woman.

But my country is home to more than just the Black American people. It always has been, and that fact is both its greatest strength and the evidence for its greatest failure.

The failure lies not in our diversity as a nation, but in there needing to be a second Independence Day for Black people on American soil at all. When the founders seceded from Great Britain, citing its abuse, violence, and injury of the colonies, they wrote of radical human freedom meant to be affirmed, not dictated, by government and power. In another world where these principles were exercised to the fullest extent, the founders would have abolished slavery, empowered women and girls, opened their doors to immigrants from around the world, honored workers and sheltered the poor, and protected all people and their individual right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. We know that world to be a far-off theory, with the reality being that our forefathers and all who came after reproduced the dynamics they themselves sought freedom from. In this sense, Juneteenth was only the first of many reckonings that contradicted our country’s independence with its dependence on the subjugation of its people. Those reckonings range from women’s suffrage and civil rights to equal marriage and immigration. My discomfort on the Fourth, therefore, is out of the disappointment that my country has chosen to achieve a perpetual state of revolution with its independence—not against Great Britain, or any other nation, but itself.

Two hundred and forty-nine years ago, the founders believed in what I believe now. They had a people they loved, a country they critiqued, and a vision of something better. One hundred and sixty years ago, freed people insisted on making real what the founders had left theoretical, leaving a legacy of resistance that would radically redefine our home and challenge its pretty, patriotic prose on freedom and liberation for generations to come. Perhaps this is why I cannot summon any pride this weekend. The work of reckoning with what we have chosen and still choose to become is unfinished. Continuing to confront my complicated, disjointed emotions is how I can channel my passions towards shaping the next two hundred and forty-nine years. Only then can I sit back and marvel at the fireworks again.

Written by:

KaLa Keaton

B.A. African American Studies

Education Studies Scholar